My father’s love of the Orient.

Text: Basil Gelpke

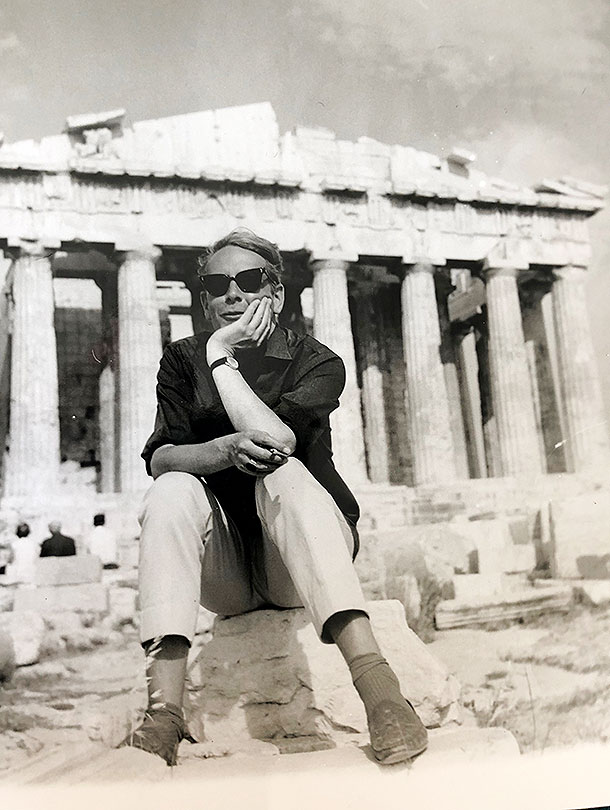

Basel Islamic scholar and drug researcher Rudolf Gelpke (1928–1972) had a lifelong fascination with the Oriental world. Reminiscences collected by his son.

My father died when I was nine years old. When he wasn’t in Tehran, he was usually traveling. I would receive postcards from him and see him perhaps three or four times a year. “If we ever find ourselves with a whole lot of time on our hands, we’ll go ride camels in the desert,” he wrote to me once. He loved surprises and would occasionally appear in Basel unexpected and unannounced.

His short life was entirely informed by his love of the Orient, which he certainly romanticized to a degree. He was no stranger to its harsh realities, but perhaps his idealized view sprang not so much from the Orient itself as from the fact that it was the antithesis to the sobriety of his native Switzerland. While ever conscious of his Western roots, he loved the Orient to the point of becoming almost assimilated. He kept his diaries mostly in Farsi, for instance. Linguistically, too, Persia became his second, adopted homeland.

A man of words

My father was born and raised in Waldenburg in the eastern part of the Swiss canton of Basel-Landschaft, the son of National Council member and Rhine shipping pioneer Rudolf Arnold Gelpke. After graduating from high school, he attended lectures on literature and philosophy and traveled extensively. Subsequently, he pursued Islamic Studies at the University of Basel under Professor Fritz Meier, a leading expert on Sufi mysticism and Oriental manuscripts. My father had discovered his passion in life. After he had completed his doctoral degree and obtained a qualification to teach at university level from the University of Bern, he embarked on a full-blooded research career that involved travels and expeditions, publications and translations of contemporary as well as classical texts.

A man of words, he left behind unpublished manuscripts, lectures, essays, and hugely prolific diaries. One of his greatest achievements was to promote understanding by not only pinpointing cultural differences but also explaining the reasons behind them. One of his major themes was the clash of cultures inevitably brought about by globalization, which was becoming apparent at the time. This he referred to as “the spreading of a uniform civilization.”

In his 1966 book Vom Rausch im Orient und Okzident (“On Intoxication in the Eastern and Western Worlds”) he writes: “Even if a person from the East adopts outward manifestations of Western civilization, its intrapersonal premises will nonetheless remain alien to him. This is what creates all the tensions, conflicts, contradictions, and chaotic conditions that are so characteristic of the Orient today.” He predicted that the “outward Westernization of the world” would be followed by an “inward Easternization of the West.”

Islam and nationalism

In 1962, my father became Professor of Persian Language and Literature at the University of California in Los Angeles, a position he would abandon less than a year later, however. In the early 1960s, California represented the polar opposite of life in the Orient. He felt deeply uncomfortable in an environment of optimistic modernity and academic career paths, preferring to devote his time to studying what he was really interested in. Above all, he once again felt drawn to Iran.

Back then, the West did not yet perceive Islamism as an issue, but was instead concerned about the Pan-Arab nationalism promoted by Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser, under whose leadership Syria and Egypt joined in 1958 to form the United Arab Republic. Nasser maneuvered skillfully between Moscow and the West, over which he achieved a moral victory in the Suez crisis despite military defeat. His concept of “Islamic Socialism,” however, was flatly rejected by Egypt’s Muslim brothers, who were already influential at that time.

In an unpublished essay on the incompatibility of Islam with nationalism, my father describes developments that are affecting us once again: “Only followers of nationalist religions could even conceive of their own nation as ‘the chosen one.’ Islam knows no such concept; it discriminates not between nations or tribes but exclusively between believers and unbelievers, with all believers being brothers. In their community, nationality, race, and social background are no longer meant to be determinants.” However, he also says that Islam “might one day bear out the dictum that it has a momentous spiritual mission to fulfill.”

Mystical experiences

The recurring theme throughout my father’s life was his spiritual quest, not so much for the meaning as for the essence of Creation, of time, and of that which lies “behind the curtain” of our everyday perceptions, as he was fond of saying. His was a desire to overcome dualist, divisive world views, but also to attain a mystical experience of life. In this connection, too, he was a translator – a translator of texts, materials, insights, and creeds from various periods and cultural regions.

Essentially, my father saw himself as a mystic who drew his inspiration from Western and Eastern sources alike. In Iran, he was drawn particularly to Sufism, the mystical branch of Islam, and in 1967, on his second marriage, this time to an Iranian, he converted to Shia Islam and adopted the name Mostafa Eslami. He took an interest in the mystical orders, whose members were often craftsmen, merchants, civil servants, poets or scholars, who privately and secretly dedicated their existence to an exclusively inward-looking form of religiousness without any sense of mission. Allied to this was his fundamental criticism of the West, particularly of its unfettered belief in progress, which he felt left no room for contemplation and spirituality.

Finally, my father’s interest in drugs as a key to mystical experiences stemmed both from experiences he had had early on with hashish and opium and from his later friendship with Albert Hofmann, the Basel-based discoverer of LSD. The two carried out self-experiments together, which my father referred to as “travels in the universe of the soul.” For him, psychoactive drugs were inseparable from his fascination with the Orient. It was through this fascination and by looking “behind the curtain” that he felt he could follow his calling to find some deeper meaning to our limited span of life on this planet.

More articles in the current issue of UNI NOVA.