Field research on top of the world.

Text: Angelika Jacobs

The Arctic is warming at an above-average rate as a result of climate change. Which plant species are still found there today, and where? In the summer of 2023, a small research team set out on the sailing ship Nanuk to answer this question.

Adapt, move or die out. In a climate that is evolving ever more rapidly, species communities are being forced to choose. Plant life in cold regions such as the Alps and Arctic is under particular pressure. Sabine Rumpf and her team are researching where certain species are still growing and how rare they have now become. To do so, they are following the tracks of three expeditions that first recorded the flora on Svalbard up to 100 years ago. By comparing their data with that of the expeditions, they aim to help better assess the climatic future of species communities in cold regions around the world.

In July and August 2023, the team sailed with the Nanuk to around twenty locations on Spitsbergen, collecting the latest data on Arctic vegetation.

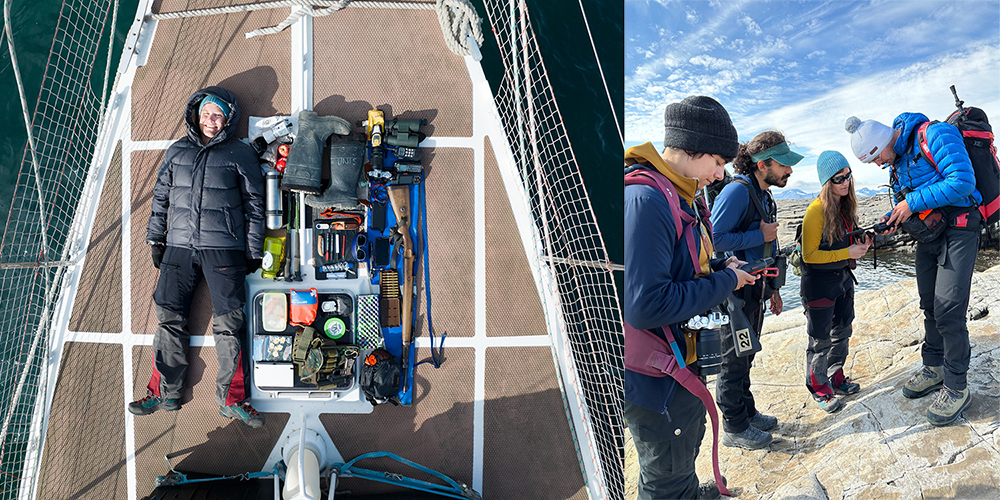

In addition to food supplies and sturdy footwear, Sabine Rumpf and her team members carry a day pack containing a GPS device, satellite phone and weapons. Everyone has to carry a weapon on Spitsbergen since there is always a chance of encountering polar bears, and that can prove fatal.

The team – (from left to right) doctoral candidate Sophie Weides, field assistant Hakîm Schepis, Professor Sabine Rumpf and doctoral candidate Raphael von Büren – follow the coordinates that researchers used to gather data 14 years ago along the tracks of the original expeditions from the last century.

The researchers systematically comb the slopes of seven Spitsbergen mountains. They record the highest and lowest elevations between which various plant species were found. The question is, has species distribution shifted compared with the earlier data? Have any species moved higher and, if so, how far?

At thirteen additional locations, the team records which species are growing as plant communities. Someone keeps watch for polar bears at all times.

Doctoral candidate Sophie Weides investigates where a specific plant species occurs on Svalbard and whether it has already been recorded at that particular site.

The researchers use tent pegs and twine to mark out plots of one square meter, then record all the plant species they find here.

If a researcher is unsure of a species, they mark the spot with a pen so that a second person can take a look. In this case, the team concludes that this is a Saxifraga hyperborea, just a bit smaller than usually found on Svalbard.

A botanist’s typical posture during field research, getting up close with a magnifying glass: To tell graminoids apart, you need to look at the tiniest details.

Sophie Weides is analyzing the team’s data as part of her doctoral dissertation: Unlike the scientists who collected the previous data, she is tracing the distribution boundaries of various species over time. How quickly do species shift their distributions? And are they fast enough to keep pace with and survive under accelerating climate change?

Field research requires a low-tech approach: Laptops and other electronic devices would suffer in the harsh outdoor conditions, so the researchers use pen and paper to record the species they find. Back in Basel, the data are digitized and used for various purposes, including modeling.

The team works to a soundtrack of melting, cracking glaciers and huge chunks of ice hitting the water. Glaciers are not the only thing that Switzerland and Spitsbergen have in common: Some species can be found in both regions, including Saxifraga cernua.

Sabine Rumpf is Assistant Professor of Ecology at the University of Basel. She researches the factors that determine plant distribution and changes in plant distribution. Her field research on Spitsbergen is funded by the Swiss Polar Institute (SPI).

More articles in this issue of UNI NOVA (November 2023).