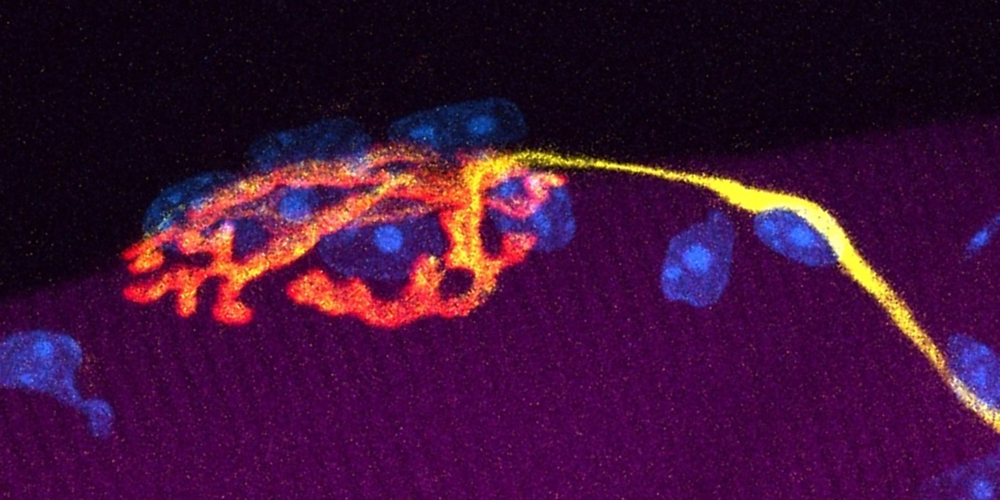

A battlefield inside the macrophage

Rabbit fever, deer fly fever or tularemia – these are only some of the names for one and the same serious infectious disease. It is caused by a highly contagious bacterium which invades the cells of the immune system and replicates within them. Researchers at the Biozentrum of the University of Basel has discovered that so-called guanylate-binding proteins bind to these intracellular pathogens and destroy them, so activating the defense machinery. The findings have been recently published in “Nature Immunology”.

17 March 2015

Who is smarter, who has the most sophisticated methods at their disposal or the best hide-away? This is the decisive question – also in the fight between pathogens and host cells. The infection biologist Petr Broz, Professor at the Biozentrum of the University of Basel, studies such dramatic battles at the molecular level. Together with researchers from the INSERM in Lyon, he has discovered that the macrophages of the immune system defend against bacterial invaders aided by guanylate-binding proteins (GBP).

Macrophages put up a fight

Francisella novicida is a bacterium with a clever strategy. This pathogen is difficult to detect for the immune system. Therefore, it can easily invade scavenger cells, called macrophages, and multiply inside the cells. “As few as ten bacteria are enough to cause an infection, which can lead to death in half the cases if left untreated”, says Dr. Etienne Meunier, the first author of this study. “As rodents are the main host, it is luckily rare for humans to become infected.” This makes the bacterium particularly suitable for studying the host’s defense mechanisms. In their study, Etienne Meunier and Petr Broz demonstrated that the GBPs in macrophages attach to the invading pathogens and destroy them. In contrast, in cells unable to produce these proteins, hundreds of bacteria accumulate, eventually severely affecting the surrounding, healthy tissue.

“In principle, the GBP proteins have a dual action”, explains Petr Broz. “They kill the bacteria and thus prevent bacterial growth within the cell. The DNA released from dying bacteria leads to activation of a signaling complex, the inflammasome, which initiates the death of the host cell.” This in turn activates new immune cells, which should impede the further proliferation of the bacteria. The GBP proteins are a very effective weapon in the fight against Francisella novicida. The crucial requirement for their success is, however, the preceding detection of the bacterium by specific receptors of the host cell and the production of cytokines. This first step is fundamental for the production of the GBPs which initiate the immune response.

Mechanism of action not yet elucidated

The studies conducted by Petr Broz and his colleagues have elucidated another piece of the puzzle surrounding the cellular defense strategy against invading bacteria. However, there are some pieces of the complete picture still missing. “As a next step, we would like to concentrate on the molecular mechanisms of the GBPs: What part of the bacterium do they recognize? How do they function? Do they act alone or do they recruit whole protein complexes to degrade the pathogens? We still have no answers to these questions”, reveals Petr Broz. The findings could be of great interest due to their relevance to other intracellular pathogens, which may also be eliminated in the same way. This includes the pathogen causing listeriosis, for example, which is taken up through contaminated food and can lead to a miscarriage in pregnant women.

Original publication

Etienne Meunier, Pierre Wallet, Roland F Dreier, Stéphanie Costanzo, Leonie Anton, Sebastian Rühl, Sébastien Dussurgey, Mathias S Dick, Anne Kistner, Mélanie Rigard, Daniel Degrandi, Klaus Pfeffer, Masahiro Yamamoto, Thomas Henry and Petr Broz

Guanylate-binding proteins promote activation of the AIM2 inflammasome during infection with Francisella novicida

Nature Immunology (2015), doi:10.1038/ni.3119