A rediscovered opponent of the Reformation.

Text: Christoph Dieffenbacher

The Basel poet and humanist Atrocianus wrote a number of polemical works attacking the Reformation – to no avail. He was then forgotten. A research team has now published the first critical edition of his printed works, with a German translation and commentary.

It was a time of great turmoil, which left a deep impression on those who lived through it. Priests refused to preach; images of the saints were secretly stolen from churches and monasteries; meetings and private Masses degenerated into brawls. Finally, in February 1529, church ornaments were smashed and crucifixes and altars were removed from the cathedral by militant evangelicals in Basel, who burned the wood on great carnival bonfires. This outburst of iconoclasm marked the triumph of the Reformation and its leader, Johannes Oecolampadius, in Basel. The bishop was forced out.

A poorly documented life

This religious and social revolution had been preceded by years of debates, involving the active participation of large numbers of humanists through their writings, polemics, and sermons. The church came under fierce attack. One of the opponents of the new teachings – later to find himself on the losing side – was Johannes Atrocianus, who defended the church in his literary and political writings and repeatedly attacked the Reformation.

After several years of work, a team at the University of Basel has now published the first complete edition of Atrocianus’s works, with a German translation and commentary. “Up until now, this writer has been largely forgotten – as we know, history is written by the winners,” says Professor Henriette Harich-Schwarzbauer, a Latinist at the University of Basel and one of the work’s co-editors, along with Dr. Christian Guerra and Dr. Judith Hindermann.

Combative personality

Even assembling the few pieces of biographical information that we have for Atrocianus was no easy task. As the researchers show, Atrocianus is to be identified with Johann Grimm, who, like other humanists, translated his name into a Classical language. “Atrocianus” is derived from the Latin “atrox” (harsh, stern, fierce) – and it was a name that suited Grimm’s combative personality. The issue was complicated by the fact that, for a long time, the author had been wrongly identified with two other people bearing the same name.

The facts of Atrocianus’s life have now been pieced together, more or less. Born in Ravensburg in the mid-1490s, he studied in Vienna and, in 1513–14, at the University of Basel. He then worked as a schoolmaster and private tutor in Basel and St Gallen. From 1528, he was based at the Augustinian collegiate chapter of St Leonhard in Basel. Following the triumph of the reformers, Atrocianus left Basel in the spring of 1529, along with others – including his printer, Johannes Faber. With his wife and two sons, he settled first in Colmar – probably until 1535 – and then in Catholic Lucerne, where he was head of the Latin school at the city’s Discalced Franciscan monastery from 1543.

A time of change

Atrocianus’s career reflects the contact networks that existed between scholars at the time. This is evident from his collection of epigrams, a poetically ambitious work. The main things that attracted him to Basel were the city’s university and its famous printers. Here, he was also in contact with leading humanists such as Erasmus of Rotterdam, Johannes Froben, Beatus Rhenanus, and Bonifacius Amerbach. As the revolutionary changes unleashed by the Reformation intensified in Basel during the 1520s, these humanists came into conflict with one another more and more. Atrocianus concentrated his fire on one person in particular: Johannes Oecolampadius, later the city’s successful reformer.

Atrocianus recognized that the clergy were guilty of abuses such as debauchery, gambling, and the sale of indulgences – and criticized them for it. However, he argued that these problems could be solved only within the institutional church itself. What his works called for was internal change, rather than schism and the establishment of a new confession.

As an opponent of the new faith, Atrocianus became increasingly disillusioned in his later writings, until finally he left Basel. From library catalogs, the Basel Latinists were able to confirm that his works probably had a limited circulation – mainly in southern Germany – and disappeared into the archives fairly quickly. However, the fact that the successors of the reformer John Calvin in Geneva, such as Theodore Beza, were familiar with Atrocianus shows that there was some awareness of the author and his works.

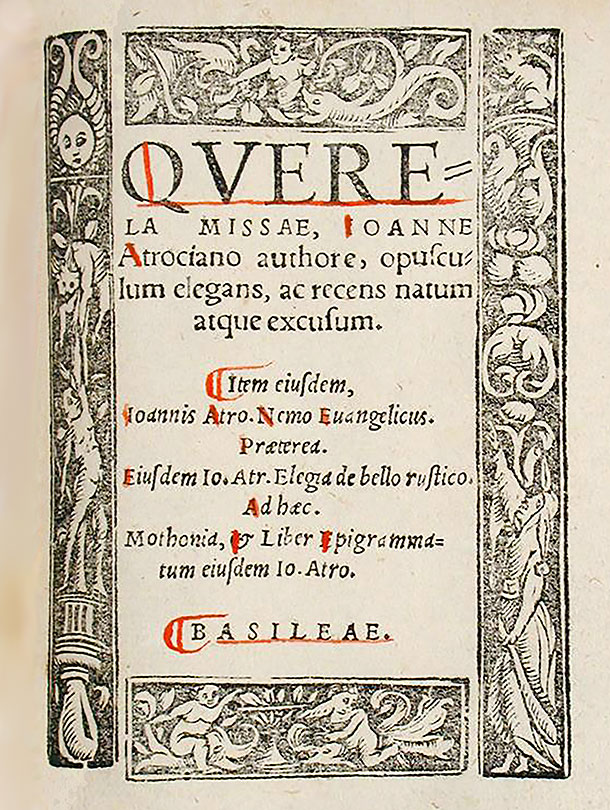

The complaint of the Mass

The works that have now been edited, with a German translation and commentary, all date from the critical months prior to the Reformation. As a result, they provide insights into this feverish period, even though many of the connections need to be explained to a modern readership. Thus, in a lengthy elegy entitled “Querela Missae”, Atrocianus presents the Mass as a woman, who bewails her fate from the grave. The traditional Mass was, in fact, abolished in Basel a few weeks after the work’s publication. The Reformation had prevailed.

Atrocianus believed that the ideas of the Reformation were also to blame for the peasant uprisings of 1525, which are described from a moralistic point of view in his work “Elegia de bello rustico”. Here Atrocianus praises peace and mourns for the many fallen peasants whom he sees as having been led astray by a false teacher (meaning Luther). In other texts, he attacked the general anti-intellectualism that he saw all around him. The humanist canon was being forgotten, he complained, and pupils were being led astray by their teachers.

Early modern Latin: An under-researched field

As Christian Guerra, one of the project’s co-editors, explains, again and again Atrocianus used short scenes from everyday life to provide a vivid illustration of how the Reformation had corrupted people. “Yet this is often done in a highly defamiliarized, poeticized way, as was typical for the period,” adds his colleague Judith Hindermann. Atrocianus’s style, while simple, was often repetitive, to “hammer home” his message. When it came to translation, the main challenge was to find ways of reflecting adequately the complex theological and intellectual connections in the texts.

“The Reformation period on the upper Rhine is well researched, on the whole, but Atrocianus’s voice has been ignored up until now,” Harich-Schwarzbauer says. This edition, which also draws on the expertise of theologians and historians, is intended as a stimulus for further research. According to Harich-Schwarzbauer, there are still “a good number of discoveries to be made” in Basel – mostly texts from this period that were written and published in Renaissance Latin. This makes the language “the most extensive of Europe’s literatures still to be explored”.

More articles in the current issue of UNI NOVA.