Calculated risks.

Text: Ori Schipper

Artificial intelligence can help to predict the risk of breast cancer recurring or detect malignant cells in tissue samples. Learning machines as assistants in medical decision-making.

Chess master, painter, poet – and medical consultant: Artificial intelligence is capable of remarkable feats. And it is becoming more influential all the time – even in the field of oncology. Little wonder, since there is a growing amount of digital health data available to be processed by increasingly powerful computers.

The exact meaning behind the magic words “artificial intelligence” depends on the area of application. Yet there are some basic commonalities: At its core, artificial intelligence involves learning machines combing through massive datasets in search of hidden patterns or principles that can be used to create groups or classify data.

A third opinion

Chang Ming, biostatistician at the University of Basel, uses artificial intelligence to complete tasks such as using a patient’s personal data – including their age, other medical conditions and the treatment they received – to assess their individual risk of breast cancer recurrence. It is important to know this risk, explains Ming, because it influences the choice of treatment. Patients with a lower risk are eligible for less intensive therapies than patients with an increased risk.

Using traditional statistical models, recurrence is correctly predicted in just two out of every three cases, says Ming: “That's only slightly better than tossing a coin.” He developed a software that used the Geneva Cancer Registry's data on the natural history of breast cancer in over 13,000 breast cancer patients to learn to predict an individual patient's risk of recurrence with an accuracy of nearly 85 percent.

“The software makes an objective prediction,” says Ming. He refers to this technique as “getting a third opinion” – just like a patient or practitioner might “get a second opinion” from another physician to help them make medical decisions. “Our application isn't going to replace anybody, but it can minimize uncertainty,” emphasizes Ming.

The medical data that the artificial intelligence uses to assess the risk of recurrence consist of information that physicians routinely ask all their patients to provide. So, it would not take much additional effort to integrate the software into clinical settings, says Ming. However, in order to do that, it must first be certified as medical equipment under the law.

The software can only receive this certification once its benefits have been demonstrated by means of so-called prospective clinical studies and tested in various patient groups. That might take some time. For now, his software will be used solely for research. In the next step, the artificial intelligence will learn from data provided by thousands of young patients in Indonesia – and continue to mature.

Digitized tissue sections

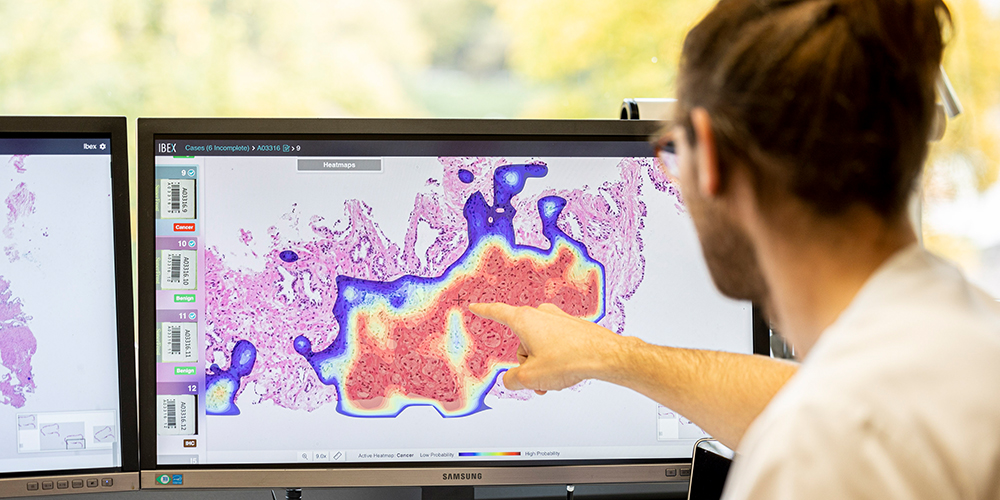

Another software based on artificial intelligence is already integrated in clinical practice: It is busily scoring digitalized images of prostate tissue samples for tumors in the Institute of Pathology at Cantonal Hospital Basel-Land.

“During my training, we were just looking at tissue samples on glass slides under a microscope,” recalls Professor Kirsten Mertz, Head of the Institute of Pathology in Liestal.

Her team started scanning tissue samples in 2016. “We were among the first in Switzerland to embrace digitalization in routine diagnostics,” says Mertz. On digitalized tissue scans, the pathologists can simply zoom in and out of any area of the tissue sample image with the click of a mouse.

To the novice, these images appear as nothing more than a cluster of cells dyed pink and purple. But the practiced eye of the expert can quickly detect where malignant cells are busy building structures that do not otherwise occur in healthy tissue. Likewise, the algorithms that Cantonal Hospital Basel-Land leases from an Israeli company are “very good” at differentiating between normal and cancerous tissue, says Mertz.

The Institute of Pathology in Liestal has been using this artificial intelligence for just over six months. Yet Mertz and her team still double-check each and every one of its diagnoses. At present, the system has yet to reduce their workload. On the contrary, it has created additional work, because they now compare all their own results against those of the artificial intelligence.

Ninety-eight or 99 percent of the time, both come to the same conclusion, says Mertz. And in cases where they disagree, it usually comes down to subtle differences, such as tumor grading, which is the system by which experts measure the biological aggressiveness and development stage of tumors.

Countering the looming shortage of skilled pathologists

These encouraging results strengthen Mertz’s hope that learning machines will soon help medical staff keep pace with the increasingly complex demands in the field of pathology – and mitigate the impending shortage of specialists. In Switzerland, this shortage – caused by a lack of young professionals entering the field – is becoming ever more apparent, whereas in other countries, it has been palpable for some time, says Mertz. “Here, we can diagnose a patient in just a few days, whereas in the United Kingdom, it can take six weeks or longer.”

There are still many legal questions to be answered, such as liability in the case of any errors made by artificial intelligence. For that reason, Mertz is active in the Swiss Digital Pathology Consortium, which aims to develop new guidelines that will help provide clarity in such matters. Yet despite the numerous unanswered questions, Mertz is convinced: “As a patient, I’d rather have artificial intelligence examine my tissue sample than have nobody examine it at all because they haven’t got the time.”

More articles in this issue of UNI NOVA (May 2023).