Working hours: autonomous workers are more productive

Text: Olivia Poisson

When the cat’s away, the mice will play – or so the saying goes. Despite the trend toward flexible working time, such as working from home and trust-based working time, these models are still the subject of concern at the management level. The economist Michael Beckmann challenges the idea that a lack of monitoring leads to idle employees.

How do different human resources strategies at companies affect their employees’ performance? Professor Michael Beckmann of the University of Basel’s Faculty of Business and Economics has been tackling this issue for several years. In his quest for answers, he uses large datasets to evaluate the various instruments empirically, focusing on measures that grant employees greater autonomy in terms of working hours. This is based on the idea that it can act as a powerful motivational tool. “I want to find out how the autonomy factor alters employee performance and what the implications of this are for management,” says the economist.

Examples of these working time models include so-called “trust-based working time” – also known as self-managed working time – and working from home, in which employees largely decide for themselves when and where they do their work. The emphasis is on completing the agreed tasks, not on being present for a specified amount of time. Recording of working hours is either wholly or partly dispensed with.

Human nature influences choice of instrument

Working from home is a particularly controversial instrument, with many employers fearing that workers could abuse the autonomy they are given. “When it comes to boosting motivation, the typical economist tends to think of performance incentives such as bonuses, performance premiums, or supervision,” says Beckmann. This view is based on a concept of human nature referred to as homo economicus, which considers humans to be rational agents that maximize utility. This is accompanied by a rather pessimistic attitude regarding propensity to work. “Homo economicus has to be given external stimulus – extrinsic motivation – to make them do as they are supposed to.”

This assumption about human behavior necessarily leads to the fear that employees only work when they are under supervision. For Beckmann, however, this concept of human nature falls short. “There are undoubtedly people who identify with their job, who enjoy their work, or who are conscientious by nature – they have what is called intrinsic motivation.” Other means are required if companies are to boost these employees’ existing self-motivation, says Beckmann, who believes that worker autonomy has great potential in this regard.

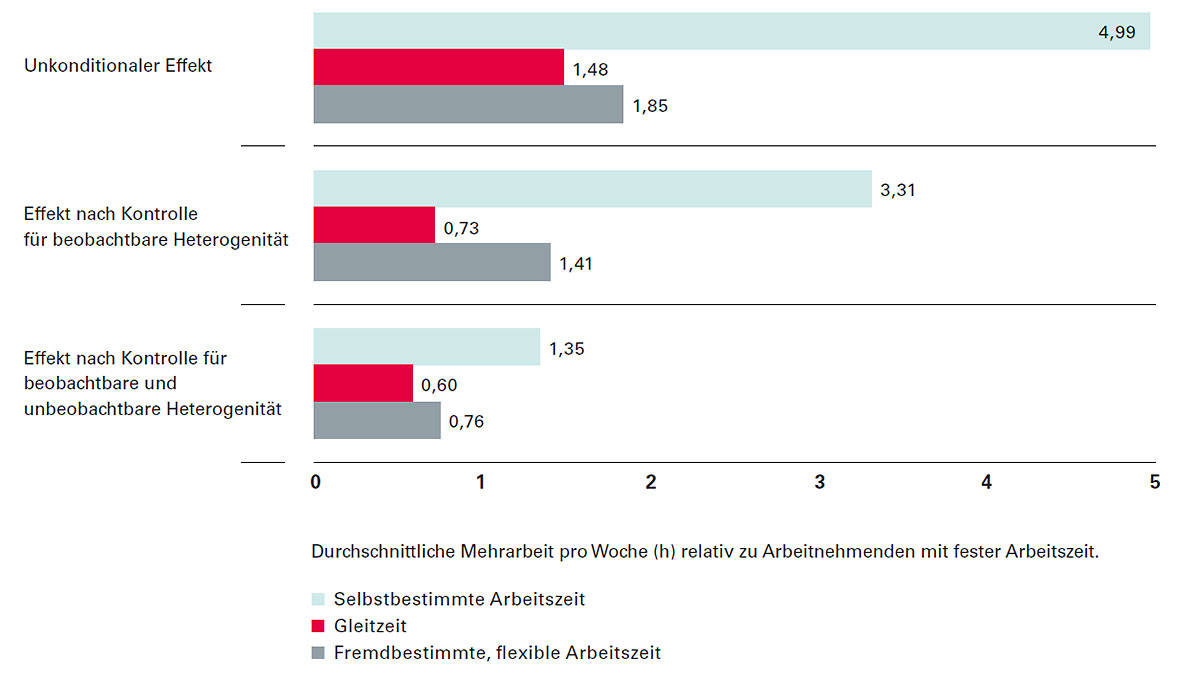

80 minutes more

This year, Beckmann and co-authors published a major study on self-managed working time. The results showed that, quite apart from working less, employees with extensive control over their working hours actually work more. Once all other factors are controlled for, employees with self-managed working time work on average 80 minutes longer per week than employees with fixed working time.

“The study clearly debunks fears that a lack of working time monitoring leads to laziness,” says Beckmann. On the contrary, it appears that, for many employees, self-management is a powerful tool for intrinsic motivation. “That is not to say there aren’t also employees who abuse their working-time autonomy – but the empirical data shows that a large number do not,” he explains.

In general, the relevance of self-managed working time models as human resources instruments increases with the employees’ level of qualifications and the complexity of the tasks. As such, the model also has its limitations, Beckmann adds. Certain occupational groups that are tied to a place of work have little chance of working from home: doctors and nursing staff, for example, or factory or construction workers.

Monitoring (often) fails, trust is (often) better

The problems begin when companies attempt to compensate for this loss of control by using monitoring instruments. Beckmann gives the example of setting over-ambitious targets: If the employees are told that they can work when and where they like, on the one hand, but that they must also meet specified goals, this can have a counterproductive effect. Often, these goals are set so high that they are not realistically achievable, or they are constantly revised upwards on a dynamic basis: “This no longer has anything to do with autonomy and puts the positive effect on performance in jeopardy.”

If companies opt for instruments based on autonomy, it is essential that they take trust seriously. Self-managed working time and working from home are only effective if there is an atmosphere of mutual trust. If the employees feel that they are being monitored, this destroys their original self-motivation.

Flexibility is more cost-effective

Despite the misgivings, working from your own home is currently in vogue. In Switzerland, too, a growing number of people are abandoning the office for at least some of the time. This is made possible in particular by modern communications technology. The office is becoming more dispensable, and many people value self-management and flexibility in the way they organize their time – especially when it comes to balancing work with family life.

“The emergence of flexible working time models also has to do with the changing nature of work. On average, work tasks are becoming increasingly demanding,” says Beckmann. Mounting competition and technological change call for a high degree of flexibility on the part of companies and employees, and the latter feel confronted with rising work demands and more flexible regulations.

Autonomy has a positive effect not only on performance; flexible working time models are also considerably more cost-effective than financial incentives as human resources instruments. For their part, the employees save time and money, as they can avoid often long commutes. For Beckmann, one thing is certain: “If the job allows it, working from home and similar models represent a win-win situation for companies and employees.”

More articles in the current issue of UNI NOVA.