A botanical collection as the culmination of a life’s work

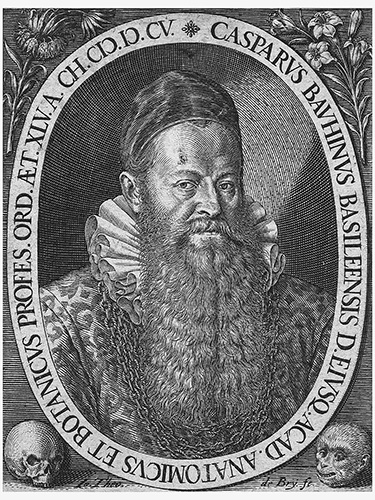

Caspar Bauhin was probably the most famous botanist of his time. The Basel-based professor collected plants from all over the world and set new standards in botany that continue to have an impact today. Now, he is the subject of an exhibition by the Department of Environmental Sciences, the University Library Basel and the Basel Botanical Society.

19 September 2024 | Noëmi Kern

Primula veris, Bellis pratensis minor, Consolida minor officinarum and Bellis sylvestris minor are just some of a total of 19 names for the same plant – the common daisy, now known as Bellis perennis L. Caspar Bauhin (1560–1624) collated these names and listed them in his publications and his herbarium. As a physician and botanist, Bauhin served as professor of anatomical medicine and botany at the University of Basel from 1589 onward.

His goal was to describe and name as many known plant species as possible and categorize them based on their similarities. To this end, he set about collecting plant material from all over the world – and made astonishing progress in this undertaking. His most important work, Pinax Theatri Botanici from 1623, lists 5,640 known plants at the time, of which he had around two-thirds collected in his herbarium.

To obtain specimens, Bauhin maintained a network of correspondents stretching throughout Europe and from North America to China. These contacts, who included politicians, physicians, pharmacists, botanists and former students, would send Bauhin parts of plants and seeds as well as the common names for them. “Descriptions or drawings weren’t enough for Bauhin. He wanted to actually see the plant so that he could characterize it perfectly,” says Jürg Stöcklin, emeritus professor of biology and botanist at the University of Basel. Bauhin listed the various designations as synonyms, including the sources.

In doing so, he put an end to the linguistic confusion that affected plant naming at the time. Moreover, he was one of the first to group all of the species into genera according to their similarities, instead of in alphabetical order. His work set new standards in botany and laid the foundation for centuries of work by subsequent botanists, such as Carl von Linné (Linnaeus).

A modern scientist

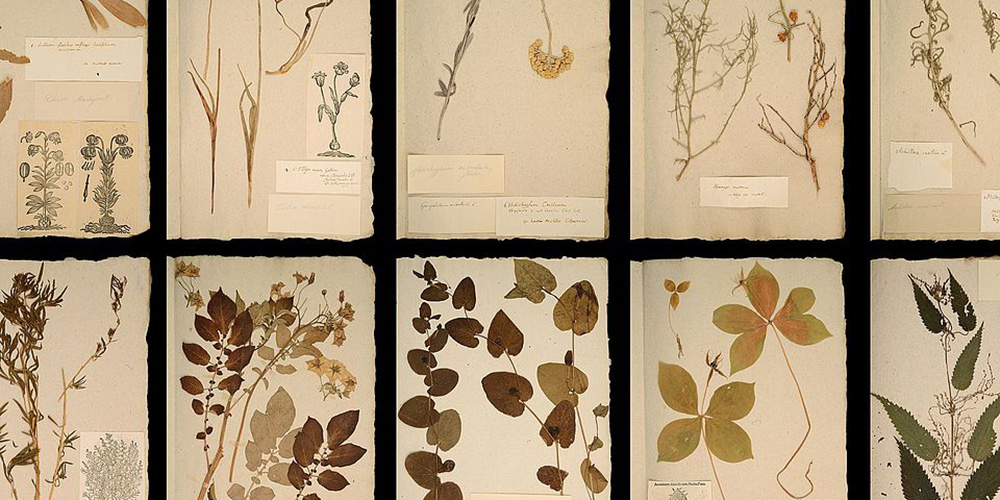

Caspar Bauhin’s herbarium became his tool for scientific work, originally comprising some 4,000 sheets, around 2,500 of which are retained to this day, containing some 3,500 specimens. Many of them came from overseas, often having made a “stopover” in another botanical garden, including the oldest remaining specimen of the potato in Europe. Bauhin cultivated the plant in his garden and, among other things, described how it could be overwintered. He also grew tomatoes and prickly pears. “Although he was a doctor, Bauhin was interested not merely in the curative effects of plants but, in general, in how many and which plants there were and how they could be distinguished and categorized,” says Stöcklin.

The exhibition not only showcases the greatest treasures of the herbarium in their original form as well as around 400 reproductions of specimens, but also traces the life and work of Bauhin. It shows that he was a modern scientist who worked empirically and meticulously, maintaining an extensive international network. “Nowadays, specimens are sometimes still exchanged as they were back then, but digitalization has made things a lot easier,” explains Dr. Jurriaan de Vos, a botanist and senior curator at the University of Basel who curated the exhibition in collaboration with Stöcklin.

Worldwide, there are about 3,500 herbaria, containing a total of around 400 million specimens, only a small proportion of which stem from the time of Bauhin or before. Of these age-old specimens, however, approximately 30 percent are from Bauhin.

Knowing what’s growing on your doorstep

The unknown plants that seafarers brought from the New World to Europe also triggered a greater interest in native flora – researchers became aware that the diversity was much greater than previously thought.

One by-product of Bauhin’s teaching work is his Catalogus Plantarum circa Basileam, a local flora of the Basel region that he created for his students. He encouraged them to go on excursions into nature and also conducted field trips himself. “Bauhin gave us an inventory of the plant world during his lifetime. This data is anchored in that era and now helps us to understand how flora change,” says de Vos. After all, plants are constantly disappearing from a region, while others – known as neophytes – are arriving.

“You can only spot changes if you know the existing inventory. Humans are dependent on plants for food, building materials and therapeutic agents, and even paper and clothing are made from plant fibers. Last but not least, they’re important for the climate,” says de Vos.

Basis for modern research

There is still considerable interest in botany today: “The master’s degree program in plant science at the University of Basel is very popular. So there will be no shortage of new botanists,” says de Vos. Thanks to digitalization and new technologies, herbaria are currently undergoing a veritable renaissance. They form the basis for global databases that allow many thousands of specimens to be analyzed at the same time. And thanks to modern technical capabilities, it’s also possible to analyze the DNA and isotopes of old specimens. This allows scientists to determine, for example, whether historic tomatoes tasted different than those that are widespread today.

Exhibition “Die ganze Welt in einem Herbarium. Jubiläumsausstellung zum 400. Todestag von Caspar Bauhin”

Vernissage on 19 September 2024 at 6 pm in the University Library Basel, Lecture Hall (1st floor). Welcome address by Prof. Dr. Primo Schär, Vice President for Research at the University of Basel, and introduction by the curators Prof. em. Dr. Jürg Stöcklin and Dr. Jurriaan M. de Vos.

The exhibition runs from 20 September 2024 to 8 January 2025. University Library Basel, exhibition room (1st floor), Schönbeinstrasse 18-20, Basel. Opening hours: Monday to Friday, 8 am to 8 pm, Saturday 10 am to 7.30 pm; admission is free.