Living in the human body

Text: Katrin Bühler

Trillions of bacteria, fungi and viruses live in our bodies. Most of them go unnoticed but infl uence us throughout our lives. When this community – known as the microbiome – becomes out of balance, illness can ensue.

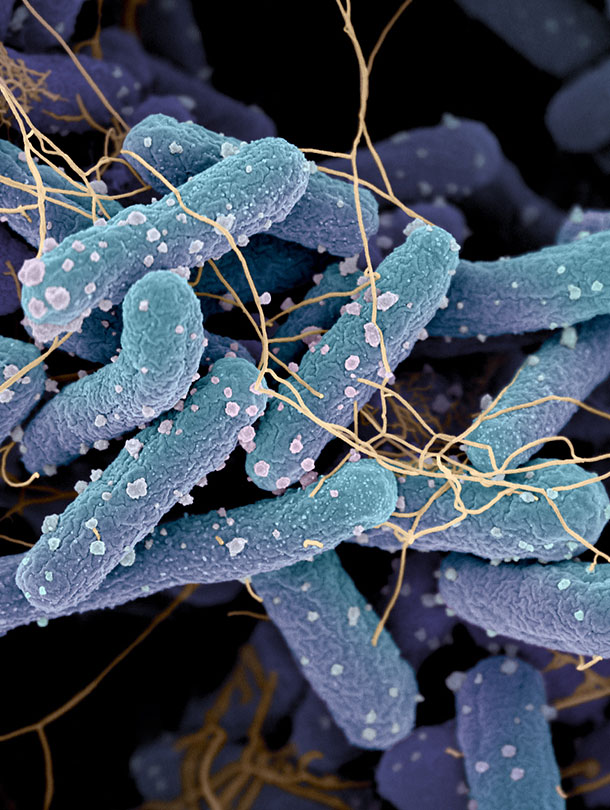

Human beings are largely dependent on microscopic residents within their body. Our skin, mucous membranes, teeth and intestines are teeming with bacteria, viruses and fungi. Our bodies host around 100 billion microorganisms in total, compared with around 30 billion human cells. Thus, we may ask ourselves who we are and, if so, how many? We all carry around about two kilos of bacteria, most of which can be found in the intestines: Just one gram of feces contains more bacteria than there are people on earth – around one trillion.

These bodily residents go practically unnoticed in our day-to-day lives. They live in peaceful symbiosis in and on our bodies, helping us to digest food, producing vitamins, and forming a protective shield against pathogens. "In the last few decades, we have learned that intensive communication takes place between microbes and our bodies," says Urs Jenal, Professor of Molecular Microbiology at Basel University’s Biozentrum. "A very close relationship has developed throughout human history that benefi ts us in various ways."

Using food more effi ciently

For example, we need the intestinal fl ora to break down plant material, something our bodies cannot do. Our microbiome provides us with around 300 times as many genes as we carry in our genetic makeup. This expands our toolbox of enzymes enormously. The more enzymes we have, the more efficiently we can use our food. Overall, intestinal bacteria perform more metabolic reactions than the human liver. Jenal comments: "Around 30 percent of the metabolic products in our blood seem to stem from our little companions."

Numerous studies show that our microbiome has a large infl uence on our health and wellbeing, for example by training our immune system in early life. With its help, our immune system learns to recognize things that are harmless and not to fight the developing microbiota as if they were foreign bodies. If specific microbes are lacking during a certain stage of development or if the microbiome changes, the immune system can quickly overreact. This can cause allergies and asthma as well as autoimmune diseases. More recent studies even point to a link between the intestinal flora and mental illnesses such as depression.

Modern lifestyles are not exactly conducive to a healthy microbiome. "By consuming unhealthy foods, we disrupt the fine balance in our intestinal flora," says Jenal. "In the case of obese people, for example, the intestinal flora changes in composition and becomes significantly less diverse. If you transfer the microbiome of an obese mouse to a mouse of normal weight, it will also become fat unless its diet is changed."

Loss of diversity

Around 1,000 to 1,400 different types of bacteria live in our digestive system, some of which are pathogenic. The overall bacterial population keeps these in check by successfully fighting them for resources. However, loss of diversity weakens the protective shield against pathogens, which can then gain the upper hand and overrun the healthy intestinal flora. These shifts, known as dysbiosis, can lead to diarrhea, stomach pains, and chronic inflammation of the intestines.

Sometimes problems are caused by members of the normal intestinal bacteria such as Clostridium difficile. "If antibiotic treatment changes the composition of the microbiome, it creates particularly favorable conditions for these bacteria to multiply and fulfill their pathogenic potential," explains Jenal. "This largely affects hospitalized patients. Sometimes fecal transplantation is the only solution. Apparently, some Swiss hospitals are already using this therapy with success."

It has been clear for some time that bacterial diversity in the intestine is decreasing. It is possible that we are in the process of shifting the balance by reducing the microbiome diversity that humans have acquired over half a million years. This theory is reinforced by the fact that indigenous peoples such as the Yanomami of South America have a much higher diversity than people with a "modern" lifestyle. "Many people believe that diversity is declining because people today are growing up in overly sterile environments. We no longer have sufficient contact with dirt and are therefore failing to gather enough important microorganisms. Excessive hygiene may thus be part of the problem."

Individual intestinal flora differs

The theory of the "disappearing microbiome" suggests that our modern lifestyle – and not least medical advances – contribute to the decline in diversity. More and more babies are being delivered by Caesarean section and fewer mothers are breastfeeding. This impairs a mother’s ability to pass on the microbiome to her child, a process that appears to be very important. "The risk of contracting asthma later in life seems to depend, among other things, on which types of bacteria colonize the intestine in the first twelve months of life," says Jenal. "Taking antibiotics in the first year of life can also impair bacterial diversity and thus the child’s long-term health." In twin studies, researchers have also established that a person’s genetic make-up plays a certain role in the composition of his or her microbiome. Every person has their own specific intestinal flora, a cocktail as individual as a fingerprint.

It really is not so difficult to do something good for your intestinal bacteria. As in so many cases, it’s all about healthy living. Exercise and a balanced diet with plenty of vegetables and vegetable fibers will help good bacteria to fl ourish and diversity to increase. And it’s never too late to change your eating habits. After all, the right conditions make community life much more pleasant.

More articles in the current issue of UNI NOVA.