Mysterious microplastics.

Text: Angelika Jacobs

Could the Rhine contain more microplastics than previously assumed? The research group “Man-Society-Environment” aims to shed light on this issue.

Plastic particles have reached even the farthest corners of the planet — and the River Rhine at Basel is no exception. Researchers led by Patricia Holm, Professor of Ecology, have been investigating microplastic contamination there for years. There is, however, a possibility that one of the existing sampling methods has “overlooked” particles of a certain size.

Environmental scientist Sebastian Rieder is therefore comparing two techniques for isolating microplastics from water for analysis. The goal would be to develop a method that could be used for longer-term monitoring of the Rhine.

Until now, the researchers have used centrifuges to isolate sediment and the microplastics contained therein from the water of the Rhine. Rieder too uses this method with 15,500 liters of river water. For comparison, however, he also passes river water through a sedimentation box with additional sieves. This sedimentation box reduces the flow speed to cause the deposition of all suspended particles.

The sediment collected from sedimentation boxes, as well as the sample from the centrifuge, are safely packed in crates and transported to the laboratory of the Man-Society-Environment research group.

There, Rieder first dries the samples in the drying cabinet (left image). The researcher then isolates the microplastics from the sample using a method known as density separation. To this end, he adds sodium bromide and water to the samples, causing organic material and microplastics to separate from the sediment and other non-organic suspended particles (right image).

After standing for a day, the material has collected on the surface (left image) and is then flushed over the rim of the flask with additional sodium bromide and water in order to isolate it (right image). Next, Rieder removes most of the organic material using the “Fenton reaction,” whereby it is converted to CO2.

Rieder places the dried samples on filter disks in a cabinet under stable storage conditions until they are analyzed.

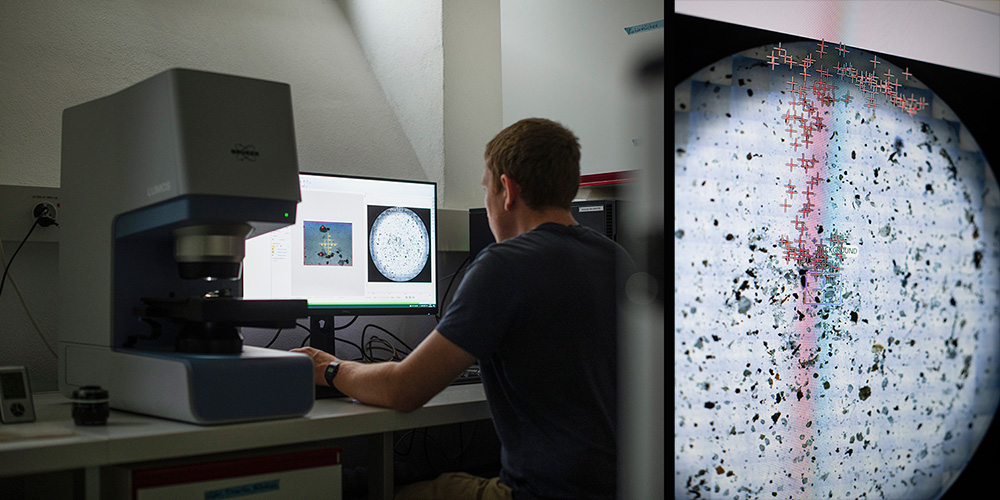

The filter disks are placed under an infrared microscope (a Fourier transform infrared spectrometer). Examining them by eye, the researcher marks any particles that might be microplastics (left image). The microscope then measures the spectra of the marked areas on the filter (right image) in the infrared beam. Software is used to compare these spectra with a database and to calculate whether they might be a plastic — and, if so, which.

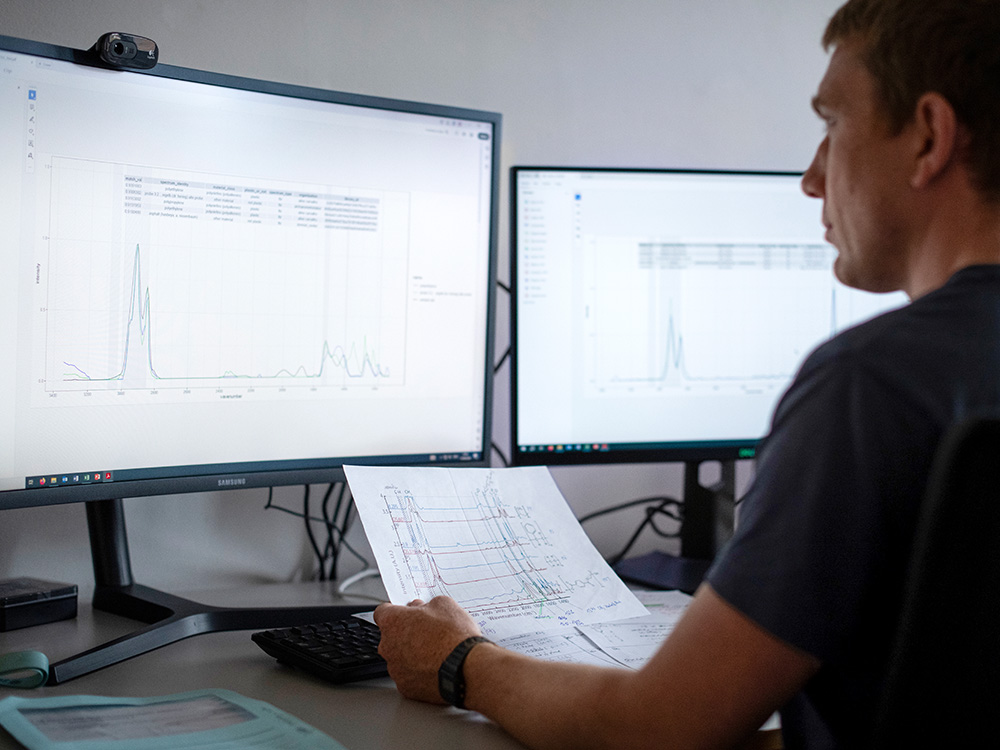

The researcher then visually reinspects any spectra that are probably microplastics but for which the software failed to find a perfect match with known spectra. Detailed analyses of the data will show whether the usual sampling method with a centrifuge leads to underestimation of the quantity of microplastic particles. On first inspection, the samples from the sedimentation box most likely also contain microplastic particles larger than 500 micrometers, whereas only particles smaller than 500 micrometers were found in the centrifuge samples.

Sebastian Rieder is a research associate in the Man-Society-Environment program at the Department of Environmental Sciences.

Patricia Holm is Professor of Ecology at the University of Basel. Her research interests include microplastics and invasive species.

More articles in this issue of UNI NOVA (November 2024).