“The war in Ukraine has deeply divided Switzerland, too”

Interview: Ivo Mijnssen

Frithjof Benjamin Schenk, Professor of East European History, on the roots of the conflict in Ukraine and how it is affecting Switzerland’s university landscape.

Professor Schenk, the civil war in eastern Ukraine continues to simmer. Why is it so hard to put an end to this conflict?

Benjamin Schenk: I think that that’s a misleading characterization for two reasons. First, the term „civil war” disguises Russia’s massive intervention, namely the provision of weapons and fighters, without which a war of this scale would never have been possible. Second, the word „simmer” belies the fact that people are being killed in eastern Ukraine almost on a daily basis. It would actually be very easy to put an end to the war: All that is needed is for both sides to keep to the terms of the Minsk agreement.

But how did what started as a domestic political conflict escalate to such an extent?

The domestic political conflict between the protesters in Kiev’s Independence Square and Viktor Yanukovych’s regime was closely linked to the issue of Ukraine’s foreign policy orientation. What set off the protests was Mr. Yanukovych’s decision not to sign the association agreement that had been negotiated with the EU. The subsequent developments – the escalation of violence, his ousting and the annexation of Crimea – are common knowledge.

What role would you say the West has played in this? Is the West partly to blame for the current situation?

All I would say is that Western politicians failed to realize in time that Ukraine’s integration with the West was Russia’s red line.

Why is Ukraine so important to Russia?

The historical perception of Kiev for Russians is as the “mother of Russian cities.” There are numerous mixed marriages; many Russians regard Ukrainian as a Russian dialect rather than a language in its own right. There are close economic ties between the two countries. Ukraine is also key to Putin’s goal of a Eurasian economic union. Besides, many Russians consider Ukraine to lie within their country’s “natural” sphere of interest. Any ties their neighbor forges with the West are seen as a threat.

It’s significant that the name Ukraine translates as “borderland”. Historically, repeated wars have been fought over what is now Ukraine. Given the circumstances, how was it possible for a sense of Ukrainian identity to develop?

The history of Ukrainian national identity goes back to the 19th century, as do the national movements in almost all European countries, by the way. After World War I and the demise of both the Tsarist Empire and the Habsburg monarchy, an independent Ukrainian state was founded, which was quickly incorporated into the newly formed Soviet Empire, though. Surprisingly, the Soviet Union was instrumental in strengthening Ukrainian identity in that it promoted nation-state structures and cadres, which would form the backbone of the independence movement in 1991.

How have the events of the past 18 months changed this identity?

Many people are saying that the war in eastern Ukraine and the struggle against a common enemy in the east have only served to cement national identity. But the question that has yet to be answered is what will happen to those in the east of the country who hold a Ukrainian passport but feel even more alienated from the government now as a result of the war and propaganda. Reintegrating these people will be a Herculean task.

The country is divided, with one half traditionally looking to the West and the other to Russia. Can that rift still be mended?

I think that the idea of a single divide is an extreme simplification. Many areas do not fit into this West vs. East dichotomy, for instance Kiev or the port of Odessa, where large sections of the population, while speaking Russian, identify with the Ukrainian national state. However, I do think that Ukraine’s nation-building project can be successful only if the fact that its citizens speak more than one language is embraced rather than viewed as a problem.

Given fundamental issues like these, people tend to seek a historical perspective. How do you feel about the growing interest in your work?

Public and media interest has definitely risen over the past year, which is a good thing, in one sense. On the other hand, I wish it hadn’t taken a war with thousands of casualties for this to happen.

Should historians even concern themselves with current political issues?

As a matter of fact, I think that far too few political scientists in Switzerland take a professional interest in the region. As for the explanatory power of history, let’s not forget that the current conflict is the result of decisions made by our contemporaries who could have acted differently. That said, there’s a tendency in both Russia and Ukraine to use history as a means to legitimize their respective stances. In this context, it’s our duty as historians to expose any clear attempt to rewrite or hijack history.

The Ukraine issue has certainly stirred intense controversy among historians of Eastern Europe. Where are the fault lines in this debate?

Some of my peers consider that we should show Russia some understanding, for instance by taking a sympathetic view of the annexation of Crimea. They accuse Putin’s critics of having an idealized view of Ukraine. On the other side are those historians of Eastern Europe who stress that comprehending something is not synonymous with justifying it.

What’s your position?

Obviously, it’s important to understand Russia and its motives. At the same time, we need to tell it as it is: The annexation of Crimea was a breach of international law, and the so-called crisis in eastern Ukraine is really an undeclared war. The sovereignty and territorial integrity of states are vital prerequisites for peace in Europe. There can be no substitute, in my opinion.

Amid all this, how is Basel’s Eastern European Studies department getting involved?

By organizing discussions and talks and through media coverage. Our events have always been well attended, with some really quite heated discussions at times. Our main responsibilities are, however, in research and teaching.

How much influence do you have?

That’s hard to tell. I’m often saddened by the number of people who come to a discussion with a closed mind. You often find a reluctance to listen and acknowledge other people’s opinions. That’s how I became aware that the war in Ukraine has deeply divided Switzerland, too. Universities can and should provide a forum for soundly researched information and robust, but fair discussion.

Let’s return to Ukraine itself. The country is still hampered by corruption and oligarchic structures. Is there a historical explanation for this?

There’s no denying or glossing over the enormous problems and challenges. Some of them are rooted in history; for instance, local politics continues to be shaped by the fact that Ukraine’s regions used to belong to different countries. However – and I want to emphasize this – history does not necessarily determine the future. It’s up to each individual to decide whether to bribe somebody or make a stand against corruption.

Do you believe that these problems will be solved?

Historians like to point out that their remit is the past, not the future. We’re having as hard a time as anyone predicting what’s going to happen. It remains to be seen whether reforms are feasible in a country at war that is investing in its armed forces and refugee relief rather than in education, anticorruption measures, and economic development.

What kind of outcome do you personally hope for?

I hope that we can remedy the lack of communication between the West and Russia, between Ukrainians and Russians, and between Putin sympathizers and Ukraine sympathizers. As Europeans, we won’t be able to meet the major challenges of the 21st century (the current influx of refugees is only a taste of what’s to come) unless we all pull together, and that includes Russia. So a speedy return to common sense and a climate of peace and cooperation would be in the best interest of the whole of Europe.

This Interview was published in UNI NOVA 126 (November 2015).

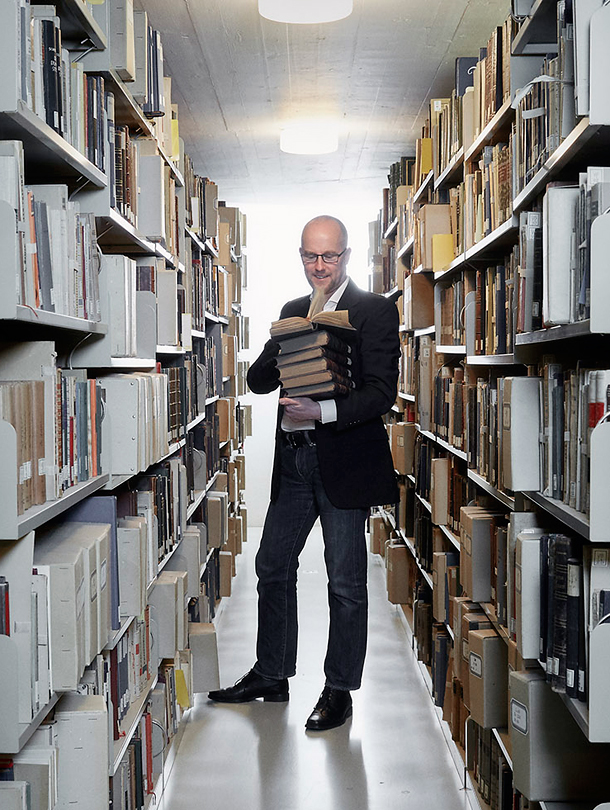

Frithjof Benjamin Schenk is Professor of Eastern European History at the University of Basel. The photo shows him in front of the Lieb collection at University Library Basel. This collection dates back to the time of Basel theologian Fritz Lieb (1892–1970) and includes around 13,000 monographs, periodicals and manuscripts from Slavic humanities, church, and economic history. The interview was conducted at the end of August 2015.