Theory of power instead of porn

Text: Urs Hafner

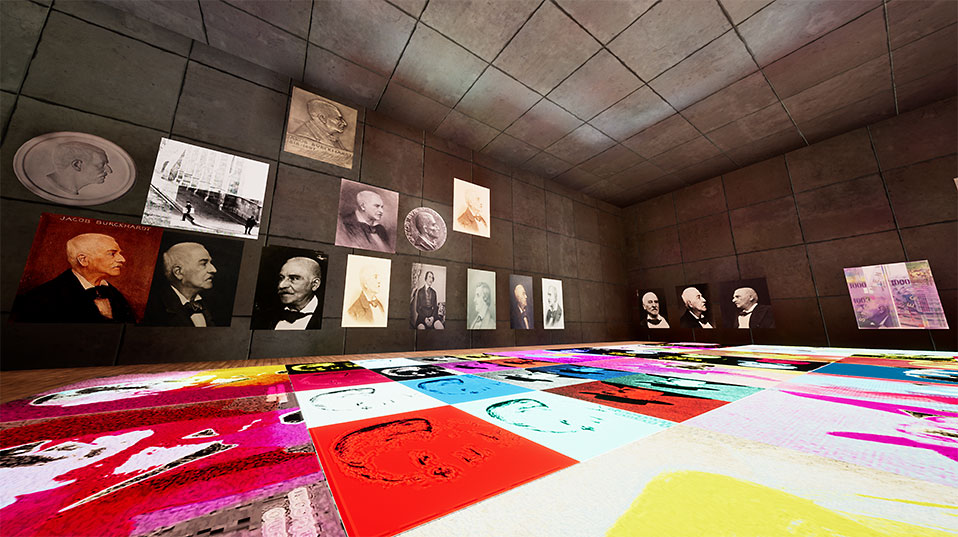

Jacob Burckhardt is going virtual. Two hundred years after his birth, the ideas of Basel’s great cultural historian are being brought to life by a 3D installation at the Basel Historical Museum.

This space achieves both: It seems to go on forever, yet at the same time it feels enclosed. It appears endless because of its towering height, its nooks and crannies, its plateaus and staircases. What makes it feel enclosed is the absence of natural light. An eerie twilight prevails here, dimly illuminated by the material itself.

The visitor sets out uncertainly across this vast expanse. In front of him, a set of giant compartments rises up toward the roof; from the right, a giant photograph of a classical sculpture fl oats toward him, and he tries to grab it with his virtual hand. Arriving at the Roche Tower, the new symbol of Basel, he enters – and is confronted by a baroque-style interior. Is there an evil monk lurking behind the buttress? Could it even be Jacob Burckhardt, the great Basel historian, who was born 200 years ago?

This space, this disturbing dreamscape that feels like something straight out of a surrealist painting, does not really exist. It is virtual. When the visitor, confused, takes off his bulky 3D glasses and has a look round, he finds himself back in the real world of the Basel Historical Museum. He is sitting at a desk surmounted by an imposing set of compartments – a reconstruction of Jacob Burckhardt’s office furniture, which is kept nearby. It was in these compartments that the historian filed his correspondence and notes, along with, perhaps, his pictures and photographs.

"The desk’s function was to organize knowledge and to imagine history," says Lucas Burkart (no relation), Professor of History at the University of Basel. It was this desk that provided Burkart and Mischa Schaub, head of the draft design research company Virtual Valley, with the inspiration for their 3D installation "Desktop". Together, with their "intervention" to mark the bicentenary of Burckhardt’s birth, they have achieved a real breakthrough in virtual technology.

A conservative nonconformist

"Desktop" transposes Burckhardt to a surreal space where he can be encountered through his ideas, his pictures and his surroundings, interwoven with the present. The installation erases the conventional distinction between present and past, the real and the virtual, without succumbing to the temptation to resurrect this conservative nonconformist in digital form.

Jacob Burckhardt was born in Basel in 1818; he died in the same city in 1897. This cultural historian, whose image adorns the Swiss 1,000 franc note, is being celebrated because his work, which deals primarily with the Italian Renaissance and Greek antiquity, has stood the test of time astonishingly well. His "Reflections on History" has long been a classic of historical theory. Burckhardt’s methodology is now seen as groundbreaking, as he relativized the primacy of the state and religion, establishing culture alongside them as a third world-historical "power". For Burckhardt, culture was "all social intercourse, all technologies, arts, literatures, and sciences" – in fact, "society in the broadest sense".

Burckhardt understood the mentality of an era as a kind of underlying structure. For a long time, this made him an isolated figure in historiography. His colleagues were mainly interested in princes and politicians, in important individuals and "reality" – as is the case once again today.

Yet Burckhardt was not just original; he was also reactionary and elitist. Developments like industrialization, mechanization, democratization and universal education horrifi ed him. He had little time for the new, liberal Switzerland. For Burckhardt, the only remaining bastion of human values in his time was high art. At the university and among his small circle of drinking companions, he created his very own sanctuary from the demands of modernity. In his letters, he expressed racist and anti-Semitic views, like some of his fellow citizens – a subject explored in part of the 3D installation.

Burckhardt – a media pioneer

And this Burckhardt, of all people, is now being launched into the new, virtual world of unlimited possibilities, a world normally populated by first-person shooters and dominated by violence and porn? Has Burckhardt been banished to his own personal hell? Lucas Burkart and Mischa Schaub reject this suggestion, citing Burckhardt’s role as a media pioneer. While his contemporaries worked exclusively with written sources, they point out, Burckhardt made innovative use of the emerging medium of photography, amassing a huge collection of 10,000 items.

According to Lucas Burkart, the Basel historian broke down the barrier between today and yesterday. "He knew that history is created by the present and provides the basis for how we approach the future." The blurring of temporal boundaries that Burckhardt envisaged is now happening in the virtual realm.

Mischa Schaub points to the triumphal march of "mixed realities": "We cannot escape the digital revolution, regardless of whether we think it is good or bad. It is happening, here and now." The two creators of the Burckhardt installation agree that soon the computer screen will be replaced by a lens that we will all wear in front of our eyes. The key issue now is to defend the content we view from technology. In other words, Burckhardt instead of bazookas?

"Desktop" is an ambitious project. It provides us with an opportunity, if we are able and willing to take it, to rediscover in the virtual realm Burckhardt’s thought – the historian himself never appears in person – as interpreted from the perspective of media theory, and then to build on that by reflecting on what is meant by history. What is the baroque interior of the Roche Tower – a vision, a warning, an "archaeology"?

And if we are unable or unwilling to do that, what will we find in this surreal landscape? Perhaps the dream we had last night. That is worth something in itself.

Virtual reality at the museum

"Desktop" will be on show at the Basel Historical Museum from 4 May until the end of July 2018, and then at the National Museum Zurich. It was put together by a four-person team from the Basel University’s Department of History and the draft design research company Virtual Valley (Lucas Burkart, Mischa Schaub, Maike Christadler and Sid Iandovka). It is freely accessible on the internet; anyone with a pair of 3D glasses can use "Desktop" at home.

More articles in the current issue of UNI NOVA.