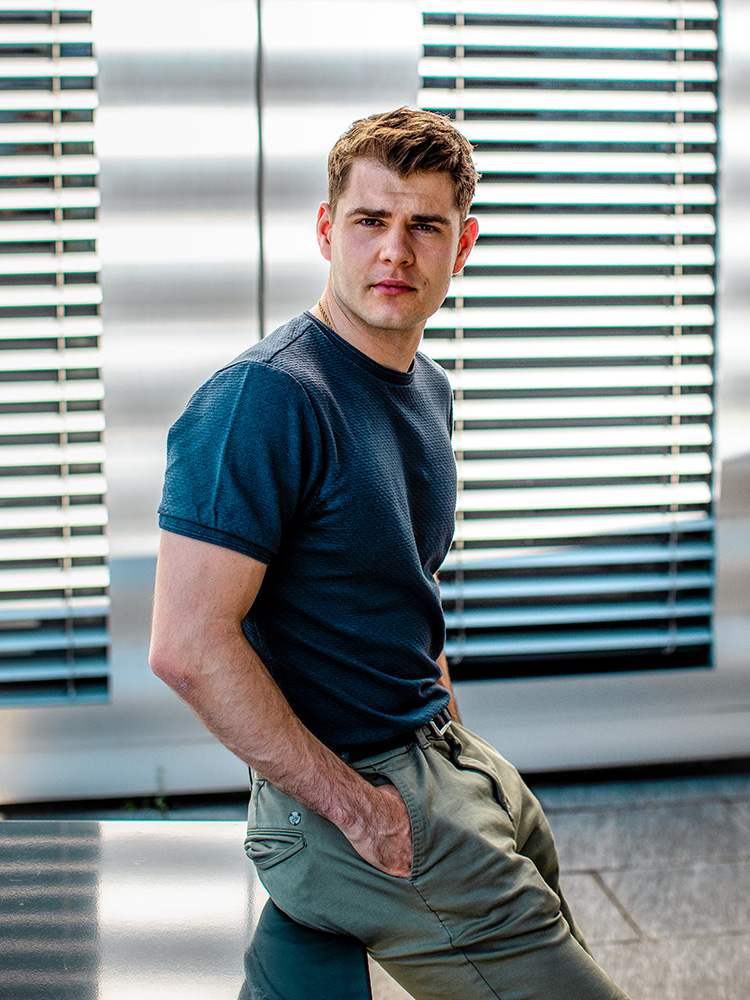

In Focus: Benjamin Jansen investigates emotional polarization in Switzerland

He thrives on variety. A doctoral student conducting research at the intersection of Swiss economy, politics and society, in his free time Benjamin Jansen travels to faraway countries to encounter exotic animals.

25 July 2024 | Céline Emch

When most people think of studying business and economics, they think of finance and marketing. So did Benjamin Jansen – as he began his studies, he would have guessed that he would find himself working for some large company five years from then. However, a look at his academic career shows that early on he developed a strong interest in another, less well-known area: political economy. It was the field in which he wrote both his bachelor’s and master’s theses – and now his doctoral dissertation as well.

Political economy uses economic theory to analyze the behavior of different actors in the political process. One example is studying the extent to which different electoral systems, such as the majority and proportional representation systems, influence the behavior of voters and politicians. Political economy also covers the analysis of factors that make civil servants more productive or corrupt. “We mostly deal with fundamental, timeless questions, and I like that. I’m not someone who has perfect knowledge of every current political detail. Instead, I’m primarily interested in systematic correlations and social developments,” explains the 28-year-old. This tendency comes from his family, who have an interest in politics. So what began as lively discussions among siblings developed into an academic career.

Parties and people

The first TV debate of the 2024 US election campaign between President Joe Biden and Donald Trump was marked by harsh rhetoric and mutual accusations that went far beyond factual criticism. Over the last decades, there has been a growing hostility between the two American parties, not only on the elite level but also among the population. In his current research project, Benjamin Jansen analyzes this phenomenon – known in expert circles as affective polarization – in the context of Swiss politics.

“The Swiss media are increasingly projecting this American development onto Switzerland, often painting a simplified picture of uniform polarization – however, reality is typically more complex,” explains Jansen. One has to distinguish between what we call issue-based polarization, which concerns disagreement on specific policy issues, and affective or emotional polarization, which goes beyond these factual differences and manifests itself in party or sympathies. In the latter, different parties not only have different political views; they also have strong reservations about the other group. As a result, debates tend to leave the factual level and become personal.

Contrary to the widespread assumption that this emotional divide between Swiss people of different political convictions is growing, the analysis by Jansen and his supervisor Alois Stutzer shows that emotional polarization in Switzerland has remained fairly stable over time. In the scope of the survey “Wie geht’s, Schweiz?” (“How are you, Switzerland?”), conducted by the Swiss TV and radio broadcaster SRG, eligible voters expressed their respective party sympathies on a scale from 0 to 10. “If someone rates all parties as 0, this person obviously has strong feelings about the major Swiss parties in general, but is not considered polarized,” explains Jansen. “The exact definition of maximum polarization can vary. In general, however, we consider a person to be highly polarized if they rate some parties very positively and others very negatively.” Based on these survey results, Jansen and Stutzer calculated an index for each person that shows how polarized they are.

Because surveys are often influenced by biases, such as a tendency towards socially desirable responses, the researchers used split-ticket votes statistics (“Panaschierstatistiken”) from the last 40 years. This data might not necessarily reflect one-to-one how the electorate feels about the parties; but it captures actual voter preferences in a fully representative and undistorted form. Combining and analyzing the two data sources produces a representative picture.

Think in models, try out in practice

On a professional level, Jansen greatly appreciates the kind of clear and simple predictions that can be derived from economic theory. However, it contrasts his personal philosophy: in private, he prefers to focus on the given here and now, because his individual life often seems too complicated to make good predictions. “That doesn’t mean that I just live for the moment and do not like to plan and organize things. For example, I consciously structure my daily life into distinct blocks. First, so I can focus on the task at hand. And second, because it allows me to mentally disengage from work in my free time,” says Jansen. For the doctoral student, these blocks currently consist of working in his office at the University and doing sports before and after.

On cocktails and coconut trees

He developed a strong preference for variety in his life while he was still a student, when he had a part-time job in a bar. He explains: “I enjoyed the contrast between the university and working as a bartender very much. Both were challenging in their own way; the bar setting helped me recover from the abstract academic world and vice versa.” He hasn’t lost his flair for cocktails and barrel-aged spirits: “Our living room at home looks like an American bar, and when I can, I still sometimes help out at the bar for former colleagues of mine.”

The doctoral student from Frenkendorf is not just looking for the exotic when it comes to rum and whiskey, but also in his travels: “I prefer coconut palms to fir trees.” Besides his general preference for the foreign, his fondness for the animal world plays a big role in his selection of travel destinations. Gorilla trekking in Uganda, a classic safari in South Africa, a jaguar tour in the Brazilian Pantanal – Jansen is fascinated by animals and likes to photograph them.

He has been particularly fond of big cats since his childhood. His personal highlight was an unexpected encounter with a jaguar in the wild, while searching on foot for an anteater. When he returns from his travels, Jansen once again focuses on the political and economic landscape of Switzerland – only a close-up of a jaguar on his computer desktop blurs the clear distinction between these two worlds.

In Focus: the University of Basel summer series

The In Focus series showcases young researchers who are playing an important role in furthering the university’s international reputation. Over the coming weeks, we will profile academics from different fields – a small representative sample of the 3,000+ doctoral students and postdocs at the University of Basel.