Basel, its population and the city walls.

Text: Jörg Becher

Historians are investigating how the spatial development of Basel since the Middle Ages has affected social life in the city and vice versa.

There is a widely held belief that “Basel marches to the beat of a different drum.” Due to its frontier location, it is said, this historic settlement on the borders of Switzerland, Germany and France has never really fitted in within the Swiss Confederation, unlike Zurich and Berne. As a center of the pharmaceutical industry and a Mecca for art lovers, the city region now has connections all around the globe. Yet at the same time, Basel is seen as exuding the comfortable charm of a small town, while its residents are said to think primarily in local terms, with an occasional tendency toward navel-gazing. Where does this blend of cosmopolitanism and provincialism come from? And what does the city’s historical development have to do with it?

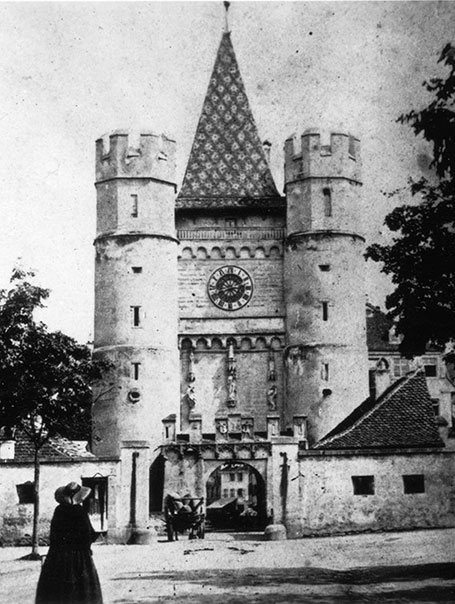

From the High Middle Ages until the middle of the 19th century, Basel was surrounded by city walls. Following the earthquake of 1356, these were rebuilt and extended, as a highly visible marker of the distinction between the city and the surrounding countryside. The city was subject to a different legal regime from the area beyond the fortifications. Even inside the walls, there were different legal jurisdictions such as Kleinbasel, which was founded as a separate town and did not merge with its big sister across the river until 1392. Special courts continued to exist in Kleinbasel into the early modern period to administer its local laws.

Farming in the suburbs

Suburbs like St Johann and St Alban also had their own justice systems to deal with minor disputes and offenses. Unlike the city center, these suburbs retained an agricultural character for quite some time.

According to Professor Susanna Burghartz, a historian who specializes in the early modern period, “there were orchards and vegetable gardens there, as well as vineyards. Small farm animals were also kept.” For example, we have records of a lawsuit in St Alban in which a swineherd was accused of not looking after the animals in his charge properly. “Or a livestock farmer may have put his dung heap in the wrong place. These were sorts of conflicts that were happening at the time,” Burghartz observes.

The city walls always had a symbolic as well as a protective function, as they separated a space that both imposed obligations on its residents and offered them legal privileges from an underprivileged, but less strictly regulated, area. In this sense, the stone ramparts always exercised a powerful influence over the lives of those within their bounds, too.

Thus, residents were not able simply to leave the city. On Sundays, in particular, you could not do anything without a pass. The idea behind this was that citizens should go to church before indulging in other pleasures, if necessary. In villages around the city such as Allschwil and Kleinhüningen, dancing and prostitution played an important role, as so-called “women’s houses” – that is, brothels – had been banned within the city walls since the Reformation.

Citizens with privileges

The period following the Reformation saw not just the imposition of stricter moral standards, but also a noticeable tightening up of the rules on naturalization. “Because citizens did not want to share their privileges, no more new citizens were created in the

18th century, which led to a significant short-time decline in the population,” Burghartz explains. Although the national borders were already customs borders, there was no real passport control. According to Professor Martin Lengwiler, who specializes in modern history, “Up to World War I, the laws governing ‘small-scale cross-border traffic’ were very liberal. It was similar to the situation today, where you can get to southern Baden or neighboring parts of Alsace relatively quickly, and often without having to show ID.”

When the canton of Basel was split in 1833, the city was cut off from its traditional hinterland. Since large areas within the city limits such as Gellert and Gundeldingen were still undeveloped, the bulk of the increase in population that occurred in the 19th century could be accommodated there. Only after about 1870, when Basel’s growth took off, did the city’s frontier location start to become a factor in town planning. Previously, its districts had not been divided on class lines; the population lived cheek by jowl, with poorer groups such as domestic servants and porters often being housed in basements, the upper stories of buildings or annexes. The phenomenon of segregation, where individual districts are inhabited exclusively by particular social classes, is thus relatively new in historical terms.

“More modest, more boring, more frugal”

Housing policy was less interventionist in Basel than in Zurich or Geneva, not least because in the city, with its humanist traditions, many things were traditionally run on philanthropic lines. At the end of the 19th century, the Gesellschaft für das Gute und Gemeinnützige (GGG; Society for the Common Good) played a particularly active role in housebuilding. Socially minded employers also offered their workers cheap accommodation. By contrast, the first municipal law providing for subsidized housing did not come into force in Basel until shortly before World War I.

Like other Swiss cities with republican constitutions, Basel had no courtly society that lived by its own rules. “Life was different without an aristocracy,” Burghartz says. “Everything was a bit more modest, more boring, more frugal. Elsewhere, by contrast, the aristocracy acted as luxury consumers and attracted scholars and artists. Still, Basel had a university that was able to take on some of that role.” Can Basel’s proverbial modesty, its oft-cited understatedness, be explained by the city’s lack of a courtly tradition, perhaps? Burghartz does not think so. Rather, she sees the phenomenon as attributable to the prevailing social attitude within a municipal entity, where no one is allowed to stand out too much. In earlier times, however, there was no such insistence on modesty. Right into the early modern period, Basel was a colorful city with many paintings on its buildings. A good example was the house “Zum Tanz”, not far from the fish market, whose facade was decorated with frescoes by Hans Holbein the Younger. Only from the 17th century onward did it become fashionable to paint houses’ facades in black and white, giving them a much more restrained appearance.

More articles in the current issue of UNI NOVA.