Remembering and forgetting.

Text: Angelika Jacobs, Illustrations: Studio Nippoldt

On the emergence and decay of memory: a journey from the first neurons to beyond death.

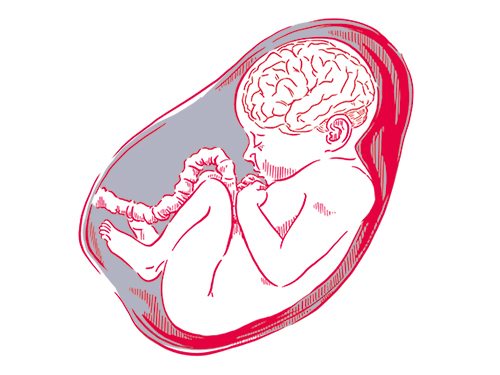

41–0 weeks before due date: Early brain structures.

The first neural precursor cells form just days after the egg is fertilized. After around two weeks, the first brain structure emerges in the form of the neural tube. After approximately 14 weeks, the hippocampus and the temporal lobes – important brain structures with a key role in memory processes – have already begun to form.

0–6 months: Facial recognition.

Babies develop the ability to recognize the faces of close family members early on, thereby demonstrating complex memory. The brain starts to form connections between neurons on the basis of perception. In the first years of life, the brain produces a surplus of these connections (synapses), although many of them are subsequently pruned.

0–2 years: Improving recall.

In the first two years of life, the amount of time babies remember things for increases steadily. At six months, they are able to imitate an observed action after 24 hours, although not after 48 hours. At nine months, they can already retain what they learn for four weeks, and at 20 months for over a year.

≈1 year: Triathletes in the making.

Learning to walk involves a type of memory known as procedural memory, which stores the movement patterns required to walk – and later to cycle or swim. This kind of memory does not need to be consciously retrieved. Accordingly, procedural memory is a subset of implicit memory, which operates at the unconscious level.

2–3 years: Earliest memories.

In this stage, explicit memory – the conscious recall of events – improves. Many people’s earliest childhood memories date back to this period or a little later, and are mostly of a special event such as a birthday party. Language acquisition is also closely linked to the unfolding of memory, allowing a child to repeat information either to itself or out loud, aiding retention.

≈4 years: Planning ahead.

This is the stage in which children develop prospective memory – the ability to remember to perform a given action at the right time. This kind of memory does not refer to events in the past, but to future intentions, and is the basis for all considered action.

6 years, from school age: Acquiring facts.

Semantic memory – the ability to retain facts – improves noticeably in this phase, as does long-term memory. This is also the life stage in which children learn to deliberately suppress memories.

12–18 years: Unforgettable teenage years.

Memories of experiences, songs, places and people from this phase of growing up are very likely to endure for 20 years – or an entire lifetime. 30-year-olds have the most vivid memories of their teenage years. In research, this is known as the “reminiscence bump”.

> 12 years: Virtual memory.

The increasing amount of time teenagers and adults spend online is not without consequences for their memory. People get worse at retaining information if they think it is just a click away – a phenomenon experts call the Google effect, or digital amnesia.

≈14–20 years: First kiss.

No one ever forgets their first kiss. This is guaranteed by two directly adjacent brain structures that play a key role in episodic memory and emotions respectively: the hippocampus and the amygdala. The interplay between these two parts of the brain ensures that particularly pleasant experiences – as well as particularly unpleasant ones – remain etched into our memory.

18–45 years: Momnesia? Sleep deprivation!

Expectant and new mothers often feel that their memory has abandoned them. This phenomenon, informally known as pregnancy brain or momnesia, is commonly chalked up to hormones, but objective tests offer no evidence of this. A much likelier explanation for the memory and concentration loss experienced by these women is relentless sleep deprivation. Hormones such as cortisol and estrogen have been shown to have an effect on the transmission of stimuli in the brain, however.

≈50 years: What just happened?

Both episodic memory and working memory, which we rely on to remember a phone number for up to a minute, for instance, begin to gradually deteriorate from as early as age 25. At around the 50-year-mark, this decline becomes much more noticeable. The upshot is that this is accompanied by gains in crystallized intelligence – the ability to learn from experience and make analogies.

≈60 years: Slowing down.

Neurons begin to decay at an ever-faster rate, although physical and mental activity, for instance in the form of social contact, can help keep memory intact for longer. Learning new skills – such as a musical instrument or a new language – remains possible even at an advanced age. However, the learning process takes longer as it becomes more difficult for information to be transferred from the short-term to the long-term memory. With increasing age, youthful memories remain vivid while those from the previous week quickly fade.

Death and oblivion.

In death, our last remaining neurons begin to die, extinguishing the physical embodiment of our recollections. All that remains is for us to become a part of the collective memory of those close to us.

More articles in the current issue of UNI NOVA.