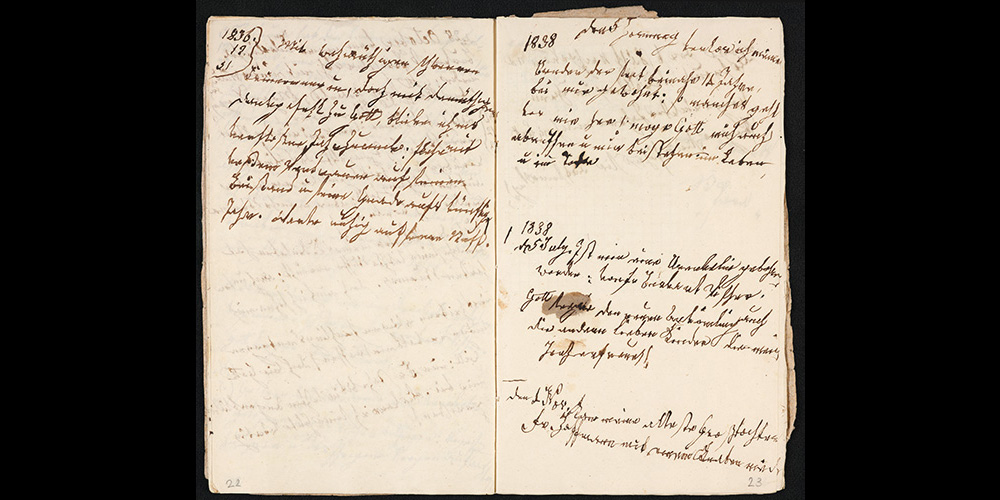

The diary of Anna Maria.

Text: Christoph Dieffenbacher

Two-hundred years ago, society was more heavily influenced by illness and death than it is today. One lady of Basel's elite "Daig" milieu recorded her thoughts on health, aging and death in private writings.

"My soul is wracked to its core, my heart bleeds; oh God, to what countless miseries you expose the mother's heart!" This dramatic prose was commended to the diary of one lady of Basel in October 1812. The entry concerned the failing health of one of her daughters, who felt death was close at hand. The diary's author gave birth to at least seven children, of which only four survived to adulthood; an unnamed eighth child died shortly before or after birth.

The author of these emotional lines came from a good – if not wealthy – household: Anna Maria Preiswerk-Iselin (1758–1840) was the second of nine children and daughter of Isaak Iselin, a renowned Enlightenment thinker, philosopher and secretary of the republic of Basel. He supported the nurturing and education of young girls. At age 18, Anna Maria entered into an arranged marriage with the silk merchant Niklaus Preiswerk, a practice that was not uncommon at the time.

Founding a girls’ school later in life

Yet the union was not a happy one, and following a solid 20 years of marriage, the pair separated – at least in terms of physical location. From then on, she ran the household of the St. Apollinaris estate near Folgensbourg in Alsace while he continued managing his business affairs in Basel.

Anna Maria was widowed at the age of 57. She maintained a modest, frugal lifestyle and later in life devoted herself to the education of her grandchildren. In addition, she engaged in charitable activities and wished to "do something useful." The project she intended to pursue in old age was a girls’ school that would transform Basel's daughters into proper housewives through education. Yet she was never able to realize this dream.

It is not known what prompted her to put quill to paper and record her thoughts and observations. Perhaps she was inspired by her father, who had written a "Parisian diary" of his own, which, it must be noted, better resembles a travelogue than a diary. "At first, against the backdrop of the smoldering conflict with her husband, she was likely inclined to write from the heart," suggests Selina Bentsch from the Department of History at the University of Basel. The author felt that the circumstances surrounding the separation needed to be recorded. This, she set forth in her diaries, was done "so that I may allow my children to know me better than ever they might by speech alone."

For Bentsch, these volumes are a rich source of material for her research. The doctoral researcher aims to uncover how a woman from Basel's urban elite perceived sickness, aging and death – privately, within her family, and in her social circle.

The author's diaries span a period of over four decades from 1795 until one year prior to her death. Her entries were sporadic at first but became more frequent as time went on. Historian Bentsch also consulted additional sources, such as letters, eulogies, funeral registries, wills and other documents.

"Ghastly appearance"

As the years passed, Anna Maria took note of her waning strength and faltering memory. At just 55 years of age, she considered herself ugly due to her "ghastly appearance", and consequently, she rarely ventured out into society anymore. It would be impossible to verify this harsh judgment of herself, as there is no portrait of her in the family archive. "That's probably no coincidence," suspects Bentsch.

What is more, the writer was plagued by her "diminishing hearing", which prevented her from attending mass. She was forced to read the sermons afterwards at home. Thankfully, she seems to have retained her vision until the age of 75.

When she was feeling under the weather, Anna Maria would undergo a procedure known as bloodletting. This practice of withdrawing blood from patients was widespread from classical antiquity through to the 19th century. Older people in particular were believed to suffer from an excess of blood (plethora). Bloodletting was thought to help in cases of "hysterical" illness and melancholy. Medical consensus also held that illness and infirmity were unrelated to gender – there was no official recognition of age-related ailments that were specific to women.

Anna Maria engaged in tireless self-reflection and observation, recording the physical and psychological manifestations of the aging process in her diary. She witnessed how childbirth threatened the lives of both women and children, and in later years, endured the death of ever more people her own age. Anna Maria was not afraid of death; indeed, as was commonplace at the time, she expected to be reunited with her deceased loved ones in the afterlife, the place in which the soul is liberated from all bodily suffering.

Her diary entries reflect the view that body and soul are capable of mutual interaction. She identified the cause of suffering not only in the failure of the body to recover, but also in a lack of spiritual fortitude.

According to Bentsch, "Anna Maria was not striving for physical self-optimization the way we view it today." In the spirit of the Pietism of the time – an ideology of which she herself was critical – it was paramount to pursue spiritual and religious perfection in life. The body was perceived as an earthly, mortal vessel for the immortal soul. In her diary, the writer alternately referred to her own body as a "husk", a "cabin" and a "prison" but also as a "machine", a sentiment that seems to herald the advent of the Industrial Age.

1250 pages in the family archive

Selina Bentsch knows some of the passages of the 32 journals totaling around 1250 manuscript pages nearly by heart. The handwritten originals, which have been almost completely preserved, are stored in a family archive in the city archives of the Canton of Basel-Stadt (Staatsarchiv Basel-Stadt).

The documents had already been transcribed with added footnotes and explanatory notes when Bentsch began digitalizing the material together with co-worker Cristina Wildisen-Münch. However, the two researchers added "tags" to the texts, created an index and published a digital edition of the diaries online.

In the last years of her life, Anna Maria wrote almost exclusively about events pertaining to her own family. Prior to that, her entries had included numerous accounts of her reading, her thoughts about the state of the world and her views on ecclesiastical and political events. Those were tumultuous times in Basel, between the French occupation, the Helvetic Republic and, later, the bloody conflicts surrounding the division of the Canton of Basel-Stadt from Basel-Landschaft after 1830.

"Diaries were nothing unusual for the urban middle class, but they weren't terribly common for women, either – the literary record is spotty at the very least," says Bentsch. She plans to compare these writings with similar journals for her dissertation. Anna Maria dictated that her diaries be read only after her death. In fact, it seemed she expected they would be. Some passages have been redacted with ink. So, whatever it was that "might have caused someone a great deal of trouble," as she writes in her diary, remains unknown. Today, her diaries are available free of charge online.

More articles in the current issue of UNI NOVA.