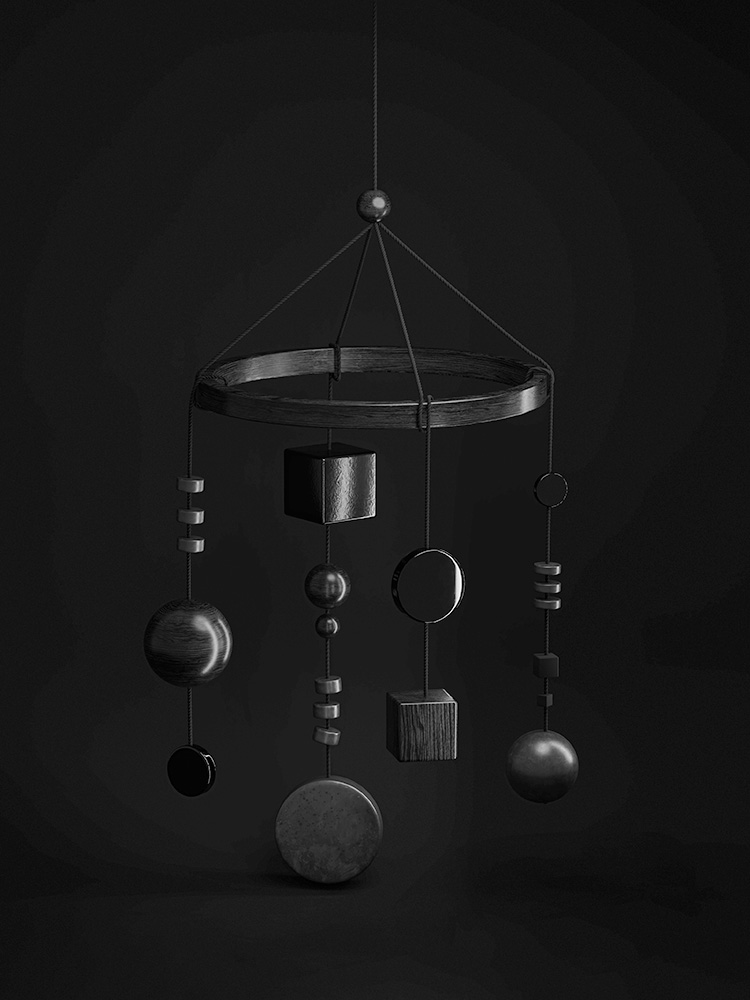

Between worlds.

Text: Céline Emch

Dreams open up a world in which the lines are blurred between day and night, light and darkness, reality and fantasy. This has inspired authors ever since antiquity.

Justus Lipsius, the Flemish humanist, sits in a Senate meeting in ancient Rome. Next to him, scholars such as Cicero, Ovid and Varro are engaged in lively debate. They are writing a code of conduct for their critics. The meeting ends abruptly – because Lipsius has awoken. It was all a dream. Or was it? He quickly reaches for pen and paper to write down what he remembers.

People have always been fascinated by dreams and their hidden meanings, and this fascination has been reflected in great stories since ancient times. Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, Virgil’s Aeneid and Dante’s Divine Comedy offer numerous examples.

“Dream narratives have long existed as a literary form, but they were actually all the rage in humanism, where we also encounter them in a satirical guise,” explains Cédric Scheidegger Lämmle, Professor of Latin at the University of Basel.

Thinking the unthinkable.

These satirical dream narratives include Lipsius’s Somnium (1581), which was particularly popular. Often written in a vibrant mix of prose and poetry known as “prosimetrum,” these narratives all have a similar plot: The narrator, often a scholar or poet, enters a dream world where he encounters and converses with prominent figures from the past. Upon waking, he documents his experiences.

Together with London-based Latinist Gesine Manuwald, Scheidegger Lämmle is studying these stories in order to produce a new, commented edition of the Somnium with a translation. The two researchers are comparing Lipsius’s work with a second dream narrative – the verses of Francesco Ottavio (also known as Cleophilus), an Italian Renaissance poet very few people have heard of today. They want the resulting book to make it easier to examine and compare the texts, among other things.

“What connects the two works is the fact that they both play with the meaning of dreams; in the dream world, the impossible becomes possible and we can think the unthinkable,” says Scheidegger Lämmle.

Hidden criticism of the present.

Like the related notion of the underworld, dream worlds are places for encounters between people living and dead. In his dream, Lipsius – who lived in the late 16th century – meets the great authors of antiquity as well as Janus Dousa, his friend and contemporary. Together, they all take part in the meeting of the Roman Senate that provides the framework for the narrative.

But this isn’t about paying homage to glorious antiquity. Instead, Lipsius aims to address the concerns of the present. The Senate concludes by adopting comically exaggerated laws for those critics of the present who in Lipsius’s time worked on ancient literature. For example, the Senate decrees that only people between the ages of 25 and 60 may engage in textual criticism.

So what is the purpose of dream narratives? “The dream is a framework for fantastical encounters with ancient literature and its creators,” explains Scheidegger Lämmle. If the hero has a question, he delves into a dream world in which people from different eras are gathered in one place, like an archive, providing advice and support to the visitor in need of information. These satirical dreams provide a space to criticize developments in the present, perform thought experiments, and reflect on oneself – always with a knowing wink.

More about dreams

More articles in this issue of UNI NOVA (November 2024).